PhD Success for Dr Bethan Scorey

We are delighted to share that on 26 June, Bethan Scorey successfully defended her thesis on ‘St Fagans Castle: its Architectural and Landscape History’. The PhD was examined by Dr Ruth Larsen (University of Derby) and Dr Euryn Roberts (Bangor University). Bethan becomes ISWE’s sixth doctoral graduate. Her thesis traces the history of the Elizabethan manor house in Cardiff, which is of twofold significance as a Grade I-listed building and home to St Fagans National Museum of History. It takes a multi-period approach which spans the sixteenth to the twentieth centuries uninterrupted, as well as a multi-disciplinary approach with interrelated sections on architecture, designed landscape, and ownership.

For Bethan, the completion of her PhD on St Fagans Castle is something of a full circle moment, as it was during her time as a Museum Assistant at St Fagans National Museum of History – an open-air museum of re-erected buildings located in the 100-acre grounds of St Fagans Castle – that she first discovered her passion for historic architecture. Bethan strongly believes that her identity as an architectural historian is grounded in her decade of experience at St Fagans, spending time in the various re-erected and re-created buildings, from an Iron Age roundhouse to a 1940s prefab, and interpreting them for visitors; “working as a Museum Assistant at St Fagans is like a crash course in Welsh architectural history” she exclaims.

After studying architecture at undergraduate level, Bethan decided to pursue architectural history at postgraduate level and enrolled on the two-year MSt Building History master’s course at Cambridge University in 2018. Her dissertation, supervised by Dr Eurwyn Wiliam, explored the history and evolution of ironworkers’ houses in Merthyr Tydfil. Bethan arrived at her PhD topic very organically, when during a six-month placement in the curatorial department at St Fagans, she was asked to research St Fagans Castle and compile a directory of all the documentary material relating to the building in the museum’s internal archives. She soon identified St Fagans Castle as a topic worthy of further study, and ISWE as the perfect institution in which to pursue it, commencing her project in September 2020 with the generous support of the James Pantyfedwen Foundation and Welsh Historic Gardens Trust. However, she has continued to work in the heritage sector over the course of studies, including working part-time as a Museum Assistant until the end of 2023. In 2021, she undertook a 4-month internship with SAVE Britain’s Heritage, an organisation which campaigns to bring new life to threatened historic buildings of all types and ages, and from 2022 until recently she was the volunteer Events Officer for C20 Cymru, the Welsh branch of the Twentieth Century Society, who campaign to save twentieth-century built heritage. Since 2024, Bethan has been the resident historian on the S4C television programme ‘Cartrefi Cymru’, which explores the history and evolution of houses in Wales, bringing architectural history to wider audiences.

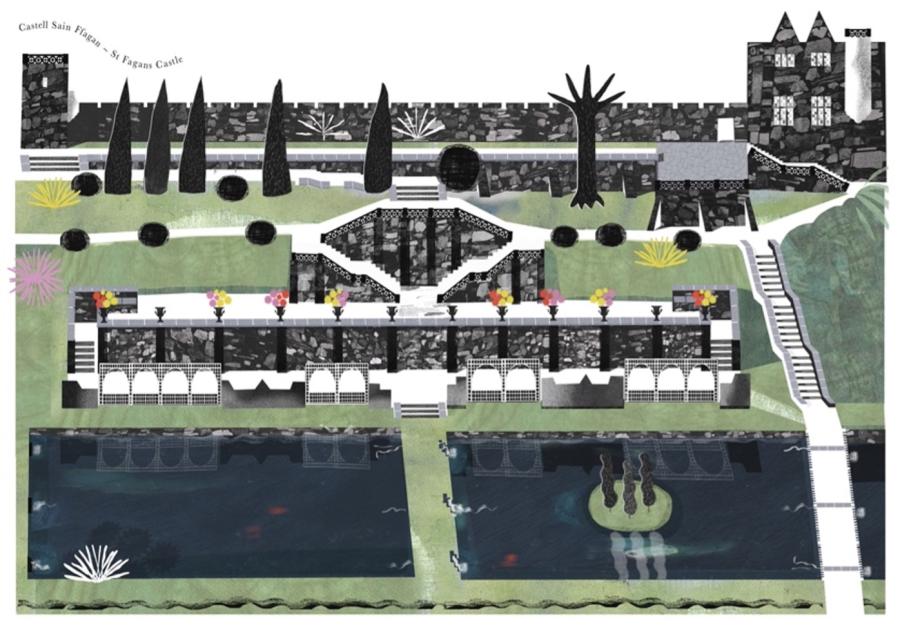

The primary objective of Bethan’s doctoral project was to provide an overdue comprehensive study of the architectural and landscape history of St Fagans Castle. Built circa 1569-80 on the site of a medieval castle and by a local gentleman-lawyer named Dr John Gibbon (d.1581), the house passed to two powerful local families in quick succession, the Herberts of Swansea in 1596 and the Lewises of Y Fan in 1616. In 1736, St Fagans Castle came into the possession of the Windsor (later Windsor-Clive) family, the Earls of Plymouth, whose main seat was in Worcestershire. Their ownership continued uninterrupted until 1946, when the house and grounds were donated to the National Museum of Wales, who were searching for a suitable site for the establishment of the open-air folk museum, which formally opened in July 1948. Despite being recognised as ‘one of the most important and unaltered Elizabethan houses in Wales’ by Cadw, there has never been an academic study of the architectural and landscape history of the building, and the only publication dedicated solely to its history is a handbook entitled St Fagans Castle and Inhabitants = Castell Sain Ffagan ai Drigolion, written by Dr Eurwyn Wiliam and published by the museum to mark the re-interpretation and re-opening of the house to the public in 1988.

Bethan's thesis takes a multi-period approach spanning the sixteenth to the twentieth century. As no written records of the various owners intentions have been left from the sixteenth to the mid-nineteenth century, Bethan has adopted a approach set out by William Whyte in his article ‘How Do Buildings Mean?’, in which he argues that instead of ‘reading’ buildings in search of a singular and fixed meaning, historians should endeavour to extract a variety of different meanings or ‘translations’, considering how the building was received and perceived over time as well as its builder’s original intentions. One of the central themes which runs through the thesis is how St Fagans Castle’s identity shifted over the centuries. For example, although it was built inside the ruins of a medieval castle, the design of the Elizabethan house broke definitively with the castle tradition. However, in the mid-Victorian period, the Windsor-Clives made additions in the Gothic and Scots Baronial style, including crenelations, turrets and a watch tower, which emphasised the antiquity of the site. Bethan thoroughly enjoyed discussing the house’s identity as a ‘castle’ with her internal examiner Dr Euryn Roberts, who specializes in the history of Wales in the Middle Ages and is particularly interested in how the medieval past is used and presented in contemporary Wales.

Most of the current literature on St Fagans can be separated into works which focus on either architectural or garden history, but Bethan’s thesis has shown that the two are intrinsically linked. One key example is the installation of Mannerist panelling to several rooms in the house in the Jacobean period, which was echoed by the installation of an extravagant lead cistern in the gardens. Bethan has also demonstrated that the mid-Victorian Servants’ Block and Terraces, previously thought to be two separate building projects, formed an ‘architectural set-piece’. The thesis also demonstrates that ownership, architecture and the designed landscape are intertwined. “I was particularly drawn to ISWE because of the expertise of my supervisors Dr Shaun Evans and Dr Lowri Ann Rees in Welsh gentry culture”, says Bethan. “Their support and knowledge has helped me place St Fagans in its broader social contexts, which has taken my thesis beyond the sphere of architectural history and has strengthened it immensely”.

In order to provide a full picture, Bethan broadened her study beyond the estate core of house, grounds, and estate buildings in the immediate vicinity to consider St Fagans Castle’s ‘sibling houses’, with a particular emphasis on Hewell Grange, the Windsor family’s principal seat in Worcestershire. “You simply can’t understand the Windsor-Clive family’s relationship with St Fagans until you understand their relationship with Hewell Grange, where they spent the majority of the year and invested the majority of their fortune”, she explains. “My thesis has shown that St Fagans and Hewell were foils to one another in every sense. While Hewell was the family’s extravagant showhouse, St Fagans was their more cosy, private family retreat”.

Bethan has found that St Fagans Castle is an excellent case study for considering broader themes, such as whether there is anything architecturally distinctive about country houses in Wales. This subject has received little academic attention compared to the architecture of country houses in England, Scotland and Ireland, with Thomas Lloyd describing it as ‘a heritage unknown’ in 1986. In fact, Lloyd’s The Lost Houses of Wales remains the only publication dedicated to the architectural history of country houses in Wales, which is extremely ironic given its subject matter! Bethan has used St Fagans Castle as a case study to critique whether there is anything architecturally distinctive about the Welsh country house, especially as compared with the English country house. However, the central paradox at St Fagans is that although it was built in Wales and by a Welshman, there isn’t anything distinctively ‘Welsh’ about the original design, which probably originated in London or the West Country of England. It is therefore extremely ironic that the later, English owners, the Windsor-Clives, engaged Welsh, provincial architects to extend the house in the Victorian period, despite their access to prominent ‘national’ architects, and the fact that these extensions were executed in the Gothic style which emphasised the site’s medieval past!

Given that St Fagans Castle was constructed circa 1569-80, a key research question is how the Italian Renaissance impacted on country houses in Wales. Bethan argues that as St Fagans Castle was built to a design created in England, it is therefore an example of a Welsh country house which fits neatly into the canon of English architecture, with a traditional tripartite plan contrived to fit behind a perfectly symmetrical façade. However, she has demonstrated that there was architectural innovation taking place in the Welsh sphere in this period – in the tradition of developing existing houses according to Renaissance fashions, thereby mediating between Welsh traditions and external fashions, as at Gwydir Castle, Raglan Castle, St Donat’s Castle and Old Beaupre Castle. Bethan was fortunate enough to present these findings in a paper at the annual New Insights into C16 and C17 British Architecture Conference in early 2024, to some of the leading scholars in the field of Elizabethan architecture. More recently, she presented a paper on the early modern history of St Fagans at the ‘Researching, Writing & Presenting Welsh Country House Histories Conference’ at Penpont, co-organised by ISWE.

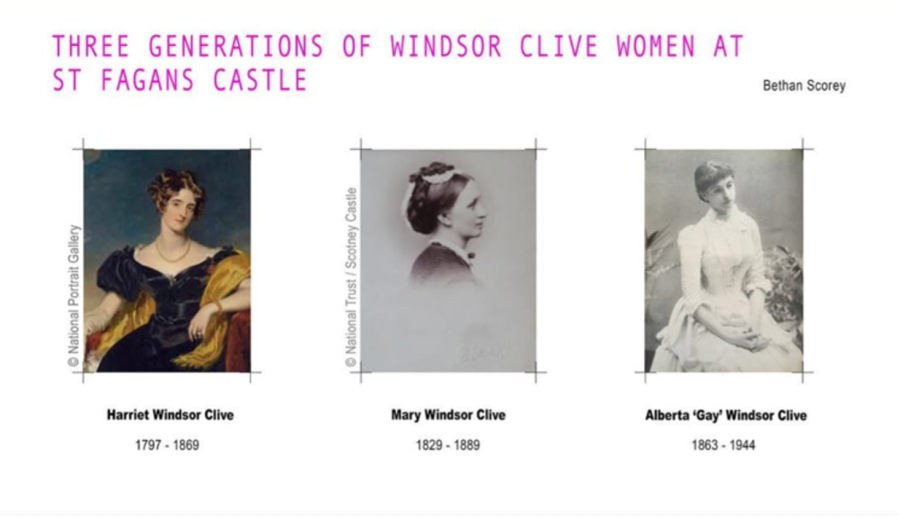

When asked which aspects of her thesis Bethan is most proud of, she replies “definitely highlighting the contribution of women at St Fagans. The current literature would have you believe that this was a male domain, but my research has found that three generations of Windsor-Clive women – Harriet, Mary and Gay – each made significant contributions to the house and gardens in the Victorian period”. In particular, she set out to challenge the portrayal of Gay Windsor-Clive as a ‘rather wonderful garden ornament’ who wandered around ‘generally beautifying the already beautiful setting’ in the 2002 publication Hidden Gardens. On the contrary, Bethan has found plenty of evidence to suggest that Gay was involved in garden-making on a very practical level, from letters to the head gardener advising on the width of paths to drawings for the estate masons. In 2023, Bethan was pleased to present a paper entitled ‘Three Generations of Windsor-Clive Women at St Fagans Castle’ at the 26th Annual Women’s Archive Wales Conference held at St Fagans, which she was able to combine with a walking tour. Bethan’s thoroughly enjoyed discussing this aspect of her research with her external examiner Dr Ruth Larsen, Senior Lecturer in History at Derby University who specialises in gender relations in the eighteenth- and nineteenth-century country house.

Another aspect of her thesis that Bethan is particularly proud of is highlighting the connection between St Fagans Castle and the notorious coloniser Robert Clive (1725-1774), often referred to as ‘Clive of India’, as well as illuminating exactly which parts of the house and gardens were built with his colonial fortune. She has found that St Fagans is an example where colonial wealth is encased in Gothic and Scots Baronial style architecture, which aligned the Windsor-Clive family with their medieval ancestors rather than the colonised country on which their wealth depended. The most conspicuous physical manifestation of the colonial connection is the Windsor-Clive balustrading, stone balustrading which comprises alternating cross and star motifs to represent the Windsor and Clive families, but which is often interpreted as purely ornamental. This particular strand of Bethan’s research aligns with Amgueddfa Cymru’s endeavours to decolonise their collections. In recognition of her research, in 2024 Bethan was engaged as a Consultant on the ‘Perspective(s)’ project commissioned by the museum in partnership with Arts Council Wales.

So, what’s next for Bethan? Although her doctoral project has drawn to a close, she will remain a part of ISWE in her ongoing, part-time role of Research & Engagement Associate. She is delighted to be adapting her thesis for publication with University of Wales Press, and is looking for opportunities to continue her research on the impact of the Renaissance on gentry houses in Wales. She continues to work on ‘Cartrefi Cymru’, and is currently filming the second half of Series 2.

Bethan also works as a freelance illustrator of historic buildings. One of her recent commissions was the cover and chapter illustrations for Clive Aslet’s The Story of the Country House, published by Yale University Press. Over the past year, Bethan has been working with various heritage organisations on a commercial basis, including Amgueddfa Cymru to illustrate the newly re-erected Vulcan Hotel at St Fagans for a crowdfunding campaign; Nantgarw China Works to create a card depicting the site for sale; and UWC Atlantic College to illustrate their home, St Donat’s Castle. She looks forward to developing these relationships further and exploring other commercial illustration opportunities.

Commenting on Bethan’s success, Dr Shaun Evans said that ‘‘We are all immensely proud of Bethan’s achievements, and her contribution not just to the work of the Institute for the Study of Welsh Estates, but to the wider field of Welsh Architectural History. Bethan has produced a wonderful PhD thesis on the history of St Fagans and its families, tracing its evolution from the medieval period through to the twentieth century, and fully contextualising the various phases of its existence in local, Welsh and British spheres. Co-supervising Bethan’s PhD with Dr Lowri Ann Rees was a real pleasure – and we both learnt a great deal from her research. We are all incredibly excited about the next stage of Bethan’s career as she develops into a leading voice on the subject of Welsh architecture. Llongyfarchiadau enfawr Dr Scorey!’’