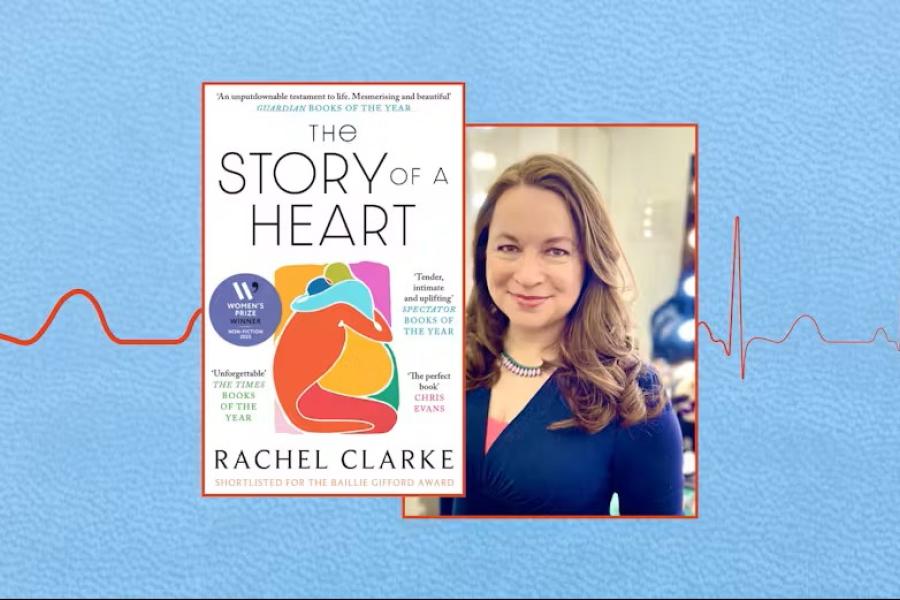

What does it mean to save a life – and what does it cost? In The Story of a Heart, Rachel Clarke answers this not with slogans or sentiment, but with quiet, searing honesty. This book, which won this year’s Women’s prize for non-fiction, is about organ donation, yes, but it’s also about family, grief, love, courage, and the astonishing edges of human experience.

At its centre are two children: Max Johnson, a healthy, active nine-year-old whose heart suddenly begins to fail, and Keira Ball, another nine-year-old – vibrant, horse-loving, full of life who tragically dies in a car accident. In a moment of unimaginable grief, Keira’s parents donate her organs. Her heart goes to Max.

A child dies. A child lives.

That is the simple, brutal, beautiful truth this book never looks away from. But Clarke does more than tell the story of heart. She immerses us in it – every breath, every monitor beep, every unbearable choice.

I read this as a health services researcher who has spent years working in the emotionally complex, ethically charged, and often hidden world of organ donation. My work explores how families navigate these unimaginable scenarios, particularly in the context of recent legislative change. Clarke’s account captures, with rare precision and compassion, the silences, the emotional labour of clinicians, and the profound weight of choice that families like Keira’s carry.

As both a doctor and a mother, Clarke brings sensitivity to every page. We feel Max’s steady decline: the exhaustion, the fear, the silence that descends as even the doctors grow unsure. We witness Keira’s final hours, the heroic efforts to save her, and the moments where unbearable grief oscillates between hope and despair, eventually giving way to a different kind of gift.

There are no easy heroes in this story, only ordinary people facing the unthinkable with extraordinary grace. Clarke brings them to life with aching clarity: the cardiologist who, in the dim light of a hospital room, sketches Max’s failing heart on a napkin so his mother can understand what words can’t explain; the ICU nurse who stays long after her shift ends, gently brushing the hair of a child who will never wake up; the donation nurse who enters a family’s darkest hour not with answers, but with quiet presence and unwavering care; the surgeon who steadies his hands – and his heart – when every second matters.

And in the chaos of resuscitation, amid alarms and broken bodies, a teddy bear is tucked beneath Keira’s arm: “Someone in the crash team has seen Keira not simply as a body, inert and unresponsive, but as a vulnerable child in need of compassion.”

The Story of a Heart is also a book about history. It’s not just about one child’s transplant, but about medicine, surgery, and the heart itself. Clarke weaves in the stories of early transplant pioneers, accidental discoveries, and the scientific stumbles and breakthroughs that built modern practice. She brings it all to life with a storyteller’s flair, making science feel intimate, alive, and deeply human.

What the heart means

What sets the heart apart, Clarke reminds us, is not just its function, but its symbolism. No other organ holds such emotional weight. “Hearts sing, soar, race, burn, break, bleed, swell, hammer and melt,” she writes. They are not just organs, they are vessels for our hopes, fears and deepest longings.

Clarke shows how, across history, the heart was seen as the source of emotion, morality – even the soul – and how that deep humanism still pulses through our language and culture today. We have our hearts broken, wear our hearts on our sleeves, and as Clarke puts it: “When trying to express our truest and most sincere selves, we do so by saying we speak from the heart, or about all that our heart desires.”

But what makes The Story of a Heart so exceptional is its emotional truth. Clarke never shies away from the pain. Max’s parents watch their son fade, terrified to even touch him. Keira’s father buys her a pink princess dress for her funeral. Max, wired to machines, records a goodbye message; we learn later he even tried to take his own life. And yet, there is light.

Keira’s sisters climb into bed with her, painting her nails and sliding Haribo sweet rings onto her fingers. Then comes a moment so clear, so quietly astonishing, it takes everyone’s breath away. Katelyn, Keira’s older sister, turns to the doctor and asks, with calm, steady eyes: “Can we donate her organs?”

This isn’t a clinical decision or a well-rehearsed conversation. It is an unprompted act of extraordinary love. These moments – fragile, generous, profoundly human – are the true beating heart of Clarke’s book.

From there, we are guided into a world so few know and even fewer ever witness: the quiet choreography that carries a gift of life from one person to another. What Katelyn sets in motion with just five words unfolds with such precision, that reading it feels like witnessing a kind of living magic.

The aftermath is just as moving. Max recovers quickly, walks again, laughs again. The two families meet. There are no big speeches, just quiet awe. And beyond that: a law is passed. Max and Keira’s Law brings in an opt-out system of donation in England. Two children. One legacy. A country changed.

And still, Clarke doesn’t let us forget the hard truths. Not every child survives. Not every family gets a miracle. Transplants are fragile. But in that fragility, she shows us, is the real miracle. Max goes fishing with his dad, the sky glows orange – Keira’s favourite colour. That is enough.

At the moment organ donation consent rates for children are declining in the UK, and there are more children on the transplant wait list than ever before. The Story of a Heart asks us to see the children, the families, and the quiet acts of love behind every donation. It’s a powerful reminder that the greatest gifts are often given in the darkest hours.

This book will break your heart – and fill it up again. It’s not just essential reading for anyone interested in organ donation and transplant. It’s essential reading for anyone who has ever loved.

This article features references to books that have been included for editorial reasons, and may contain links to bookshop.org. If you click on one of the links and go on to buy something from bookshop.org The Conversation UK may earn a commission.![]()